The CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report is part of a long history of efforts to fight death and disease with data – and it’s at risk.

Over the weekend, 700 CDC staffers faced employment whiplash as they were fired on Friday and reinstated by email the same night. Among them were members of the Epidemic Intelligence Service and the editorial staff of the agency’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. This publication usually flies under the public radar, but it’s a key piece of how the U.S. spots, tracks, and deals with emerging public health risks – from plagues to product safety. And now it’s not being released, for only the second time in its 65-year history.

Here’s what the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report is, why it matters, and why it keeps running afoul of the Trump administration.

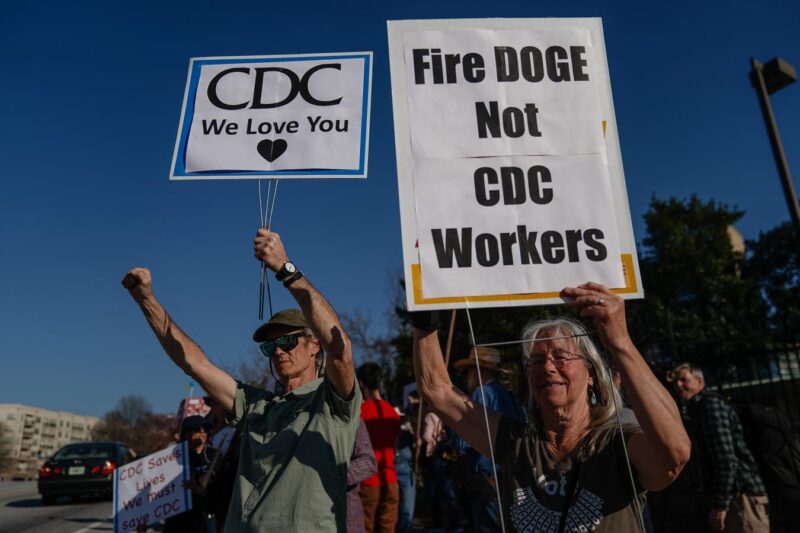

ATLANTA, GEORGIA – MARCH 12: People protesting personnel cuts at the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) hold signs outside the organization’s main headquarters on March 12, 2025 in Atlanta, Georgia. Some Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) employees have sent a letter to CDC leadership, they argue their dismissals were unfair and violated due process as they face a deadline that could officially end their employment status. (Photo by Elijah Nouvelage/Getty Images)

Getty Images

Dispatch From the Front Lines of Public Health

The CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report is exactly what it it says on the tin: a weekly newsletter from scientists at the CDC, listing deaths and diseases cases (broken down by state and city). MMWR also points out anything that seems a little “off,” like disease outbreaks, clusters of patients with unusual symptoms, or even a sudden increase in certain types of injuries.

It’s dry reading for the layperson, but MMWR is a vital dispatch from the front lines of public health for doctors and local public health officials. H1N1 flu first came to U.S. doctors’ attention in the MMWR, and so did the first reports of kids getting hurt playing the “choking game” in 2008. If there’s an outbreak of measles or a new emerging virus, your doctor will probably hear about in the MMWR first – along with information on signs to watch for and recommendations for treatment.

“To a great extent, the history of MMWR is the history of disease and injury prevention and control in the United States,” wrote physician Frederic Shaw and his colleagues in 2011 paper.

One of the best examples of how the MMWR works, and why it matters, comes from the early days of the AIDS pandemic in the summer of 1981. A pair of doctors in Los Angeles reported five patients, at three different hospitals, with pneumonia caused by a bacterium called Pneumocystis carinii. This particular bacterial infection usually only shows up in cancer patients – or people with seriously weakened immune systems. But all five of these patients had been very healthy, until they suddenly weren’t.

For Doctors Michael Gottlieb and Joel Weisman, that set off warning sirens.

All five patients showed other signs of immune system problems: their lymph nodes were swollen, they’d lost alarming amounts of weight, and their blood contained fewer white cells than it should. They also suffered from rashes, fevers, diarrhea, and even fungal infections that had taken advantage of their weakened immune systems. And all five men were gay. (Important note: AIDS can affect anyone, but the pandemic of the 1980s and 1990s hit gay communities especially hard.)

Gottlieb and Weisman knew that a traditional medical journal would take months to peer review, edit, and publish their findings, and they had a bad feeling that this was too urgent to wait. And they were right; by the time their report came out in the MMR on June 5, 1981, two of the five patients were already dead.

“Immediately after the article appeared, clinicians across the country who had seen similar patients realized the connection to the Los Angeles cases,” according to Shaw and his colleagues. “Recognition of the AIDS epidemic had begun.”

The first medical journal article about AIDS came out four months later. Even today, the CDC contends that the MMWR offers more rigorously reviewed, detailed scientific information than an unofficial statement or a press release – but faster than even the speediest academic journals can get the information out. In addition to the weekly reports, MMWR also publishes occasional updates on its website and by email, which can get data into the hands of doctors and public health officials within hours instead of weeks.

Not long after breaking the grim news about AIDS, the MMWR published the first reports of toxic shock syndrome: a sudden, severe bacterial infection often linked to leaving very absorbent tampons in place for too long. In the months after the September 11, 2001 terror attacks, the MMWR tracked the investigation into a series of letters containing anthrax, mailed to U.S. newsrooms and senate offices in late September 2001. MMWR also kept U.S. doctors apprised of the SARS pandemic in 2003 and the latest information on Covid-19 starting in early 2020.

“Such reports have historically been published with little fanfare and no political interference, said several longtime health department officials, and have been viewed as a cornerstone of the nation’s public health work for decades,” wrote Politico’s Dan Diamond in September 2020.

But that’s increasingly not been the case in recent years.

Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Zairian scientists in full protective suits collecting samples from animals, Kikwit, Zaire, 1995. Image courtesy Centers for Disease Control (CDC) / Ethleen Lloyd. (Photo by Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images)

Getty Images

‘I am sick; impossible to procure accurate data.’

Before the CDC, the United States had the Marine Hospital Service (founded in 1870). Its original job was to run Marine Hospitals, which treated sick or injured merchant sailors and Coast Guard members. But within a few years, the Marine Hospital Service wound up more-or-less in charge of public health in American port cities, at least when it came to sanitation and infectious diseases.

The Marine Hospital Service also published The Bulletin of the Public Health, a weekly report of sanitation and health aboard ships headed for the U.S., gathered from American consular offices in far-flung port cities around the world. Those reports, starting in July 1878, were the precursor of today’s MMWR (the Bulletin shut down in 1879; the Weekly Abstract of Sanitary Reports replaced it in 1887, got renamed Public Health Reports in 1896, and got renamed again to MMWR in 1952. Confusingly, Public Health Reports is now a bimonthly scientific journal, while MMWR handles public health statistics and short, urgent updates. Whew).

In August 1878, the Bulletin recorded a swelling tide of death along the Mississippi River Valley, which was clutched in the death grip of a yellow fever epidemic that would eventually kill 20,000 people.

“On August 24, 1878, the Bulletin’s published a telegram from Dr. Booth, the Marine Hospital Service officer at Vicksburg, Mississippi: ‘I am sick; impossible to procure accurate data.’ A week later, the Bulletin’s report from Vicksburg said, ‘Dr. Booth, in charge of the patients of the Marine Hospital Service, died the 27th,’” wrote Shaw and his colleagues.

Even when the doctors were dying of the very illnesses they tracked, the reports came in and the Bulletin got published. And since 1960, when the CDC took over publishing the MMWR, the data has come in and been reviewed and published every week without fail – until this year.

Gag Orders, Layoffs, and Political Reviews

ATLANTA, GEORGIA – AUGUST 28: Former Centers for Disease Control (CDC) officials Dan Jernigan, Deb Houry, and Demetre Daskalakis smile as employees and supporters of the CDC line up outside its global headquarters on August 28, 2025 in Atlanta, Georgia. The three officials were honored after resigning in the wake of U.S. President Donald Trump’s attempted firing of CDC director Susan Monarez. (Photo by Elijah Nouvelage/Getty Images)

Getty Images

The MMWR missed two weeks of publication in a row in January 2025, the first gap in its nearly 65-year history at the CDC. In late January, the Trump administration ordered a halt on all public communications from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. That order included the MMWR, which missed its scheduled January 23 and January 30 releases.

Now, for only the second time in its history, the MMWR’s offices are silent and its website sits without an update. This time, the culprit is the federal government shutdown, which started at midnight on October 1. During earlier shutdowns, a small crew of employees – deemed essential in the same way as soldiers, air traffic controllers, and and NOAA weather forecasters – has kept the MMWR up and running.

But not this time around. The CDC released its most recent MMWR on September 25, the week prior to the start of the shutdown. A single report – on treatments for tularemia – was posted on October 2. Since then: radio silence.

Amid this unprecedented (or at least, only-recently-precedented) gap in coverage came the whiplash firing and reinstatement of the MMWR’s entire editorial staff on October 10. And this isn’t the first time the Trump administration and the MMWR have butted heads. At the height of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, administration appointees attempted to wrest editorial control of MMWR from the team of scientists and physicians responsible for the publication.

Michael Caputo, then the assistant secretary for public affairs at the Department of Health and Human Services, held up a report on the risks and effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine for a full month while he questions its authors’ political views and accused scientists of trying to “hurt the President” in an email.

Caputo and his staff demanded to personally review and approve every issue of MMWR before its release, in order to bring the reports’ data and recommendations in line with administration talking points about Covid-19. Editors at MMWR rebuffed those demands, though Politico’s Dan Diamond reported in September 2020 that they did allow some review “and, in a few cases, compromised on wording.”

In that climate, especially with measles outbreaks flaring up, flu season looming, and Covid-19 still in circulation, it’s hard not to worry about the fate of the MMWR – and U.S. public health efforts overall.

As physician Sonja Rasmussen, a former editor of MMWR, told MSN’s MedPage Today in January, “If [the CDC] have information that they believe is important enough to get out in the MMWR, I, as a physician, want to be able to have that information to take the best care of my patients.”