This week delivered a sobering reminder that Alzheimer’s disease continues to defy even the most sophisticated scientific strategies. Within 24 hours, two major pharmaceutical players—Johnson & Johnson and Novo Nordisk—announced failures of their respective Phase 2 and Phase 3 programs, each representing billions in potential investment and years of work.

A Double Dose Of Disappointment

J&J’s posdinemab, an experimental anti-tau antibody once valued at over $5 billion in potential annual sales, failed to slow cognitive decline in early-stage Alzheimer’s patients. The company promptly halted the trial, citing a lack of statistically significant benefit across cognitive endpoints.

Almost simultaneously, Novo Nordisk revealed that semaglutide, the oral GLP-1 drug that helped make it a global obesity powerhouse, also missed primary endpoints in the EVOKE and EVOKE+ trials for early Alzheimer’s disease. The company’s stock tumbled on the news.

Two very different scientific approaches—one rooted in neurobiology, the other in metabolism—have now collided with the same harsh truth: Alzheimer’s remains an extraordinarily difficult, multifactorial disease that does not yield easily to single-target interventions.

The Rise And Fall Of Anti-Tau Therapy

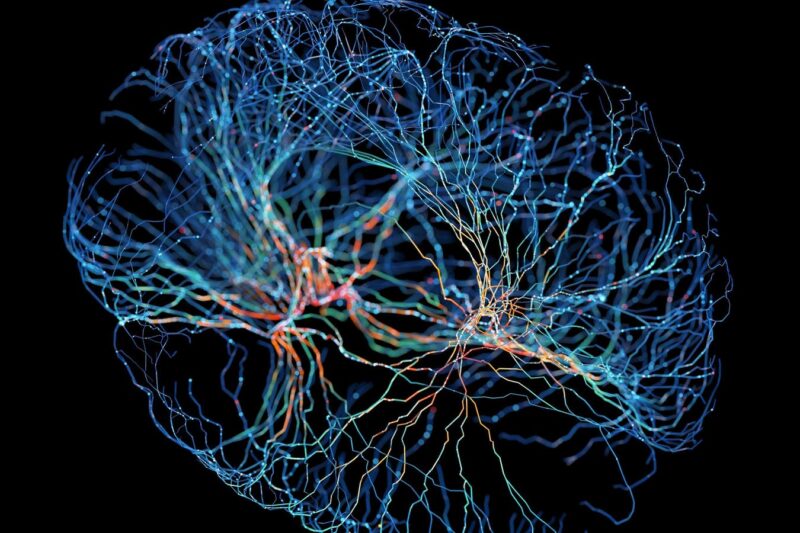

For more than a decade, the tau hypothesis has been viewed as the logical successor to amyloid-targeted therapies. Whereas amyloid plaques are thought to ignite the disease process, tau tangles—aggregated, hyper-phosphorylated forms of the microtubule-binding protein tau—appear to drive the actual neuronal dysfunction and cognitive decline.

Tau pathology also correlates more tightly with symptom progression than amyloid burden does, making it an attractive therapeutic target. In Alzheimer’s and related tauopathies, abnormal tau seems to spread through the brain in a “prion-like” manner, passing from cell to cell. The idea behind anti-tau antibodies was elegantly simple: block this spread, and you might halt disease progression.

But results in humans have repeatedly disappointed. Roche’s semorinemab failed in two large trials. UCB’s bepranemab fell short earlier this year. And now J&J’s posdinemab, which binds phosphorylated tau at pT217, joins the list.

The Autonomy trial, enrolling more than 500 participants with early Alzheimer’s, measured cognition and daily function over 104 weeks. While the drug was safe, it showed no statistically significant slowing of clinical decline. J&J discontinued development.

Novo’s GLP-1 Alzheimer’s Bet Falls Flat

If J&J’s setback represents the limits of neurobiology, Novo Nordisk’s disappointment reflects the challenges of metabolic medicine applied to the brain.

Semaglutide—marketed as Rybelsus (oral) and Ozempic/Wegovy (injectable)—has transformed diabetes and obesity care. Its mechanism, agonism of the GLP-1 receptor, improves insulin sensitivity, reduces inflammation, and promotes weight loss. Since type 2 diabetes and obesity are risk factors for dementia, repurposing GLP-1 drugs for Alzheimer’s seemed both scientifically sound and commercially irresistible.

In animal models, GLP-1 receptor activation reduces amyloid and tau accumulation, enhances neurogenesis, and decreases neuroinflammation. Observational studies even hinted that people on GLP-1 therapies had lower dementia risk.

Novo’s twin EVOKE and EVOKE+ trials tested this hypothesis in more than 3,000 adults aged 55–85 with early Alzheimer’s. The goal: determine whether semaglutide could slow cognitive decline over two years. The company reported no improvement in disease progression, despite biomarker and imaging data suggesting peripheral metabolic benefits.

Why GLP-1 And Metformin Looked Bright

The enthusiasm for GLP-1 and related metabolic drugs was grounded in decades of evidence linking Alzheimer’s to “type 3 diabetes,” a state of insulin resistance and energy failure within the brain. Insulin signaling is critical for synaptic plasticity and memory formation; impaired signaling promotes amyloid accumulation and tau hyperphosphorylation.

Drugs like liraglutide (another GLP-1 agonist) showed early signs of benefit in smaller studies. The 12-month Phase 2b ELAD trial hinted at an 18% slowing of cognitive decline and reduced brain atrophy. Meanwhile, metformin, the old diabetes standby, activates AMPK and improves mitochondrial function. Epidemiological data suggest lower dementia incidence among metformin users, though results are inconsistent.

These drugs also offered an appealing safety and cost profile. Both GLP-1s and metformin are widely used, well understood, and—especially in the case of metformin—cheap. In theory, they could provide scalable prevention tools if efficacy were confirmed.

But Alzheimer’s biology may simply be too far downstream of metabolic dysfunction for these drugs to make a measurable dent once symptoms appear. Their benefits may depend on early, perhaps preclinical, intervention or on use in metabolic subtypes of the disease.

Where The Field Goes

Despite these setbacks, the Alzheimer’s pipeline remains crowded. Bristol Myers Squibb continues testing its mid-domain tau antibody BMS-986446, and Biogen is advancing its antisense tau approach.

Meanwhile, metformin precision-medicine initiatives aim to understand patient subtypes using biomarkers like plasma p-tau and glucose metabolism signatures.

For the millions of patients and families waiting for breakthroughs, progress can feel agonizingly slow. Yet every “failure” is a data point pushing researchers closer to the complex truth of how the brain fails and perhaps, someday, how it can be saved