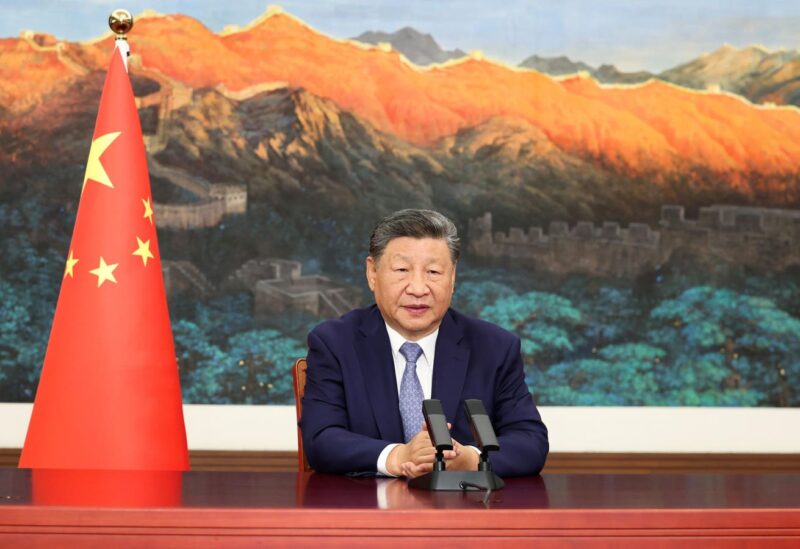

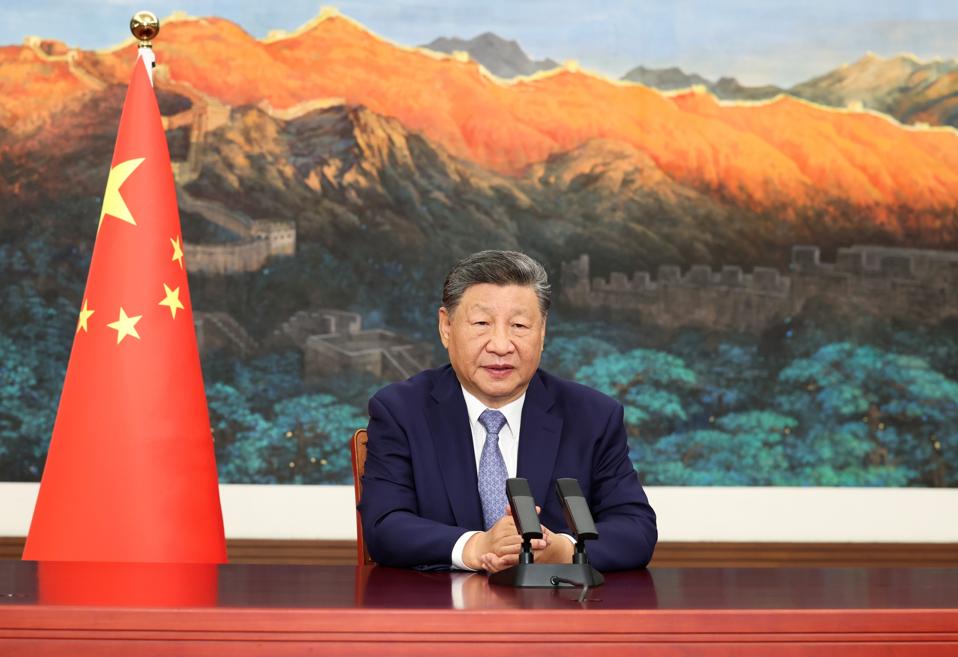

Chinese President Xi Jinping delivers a video speech to the United Nations Climate Summit 2025 held in New York on Sept. 24, 2025. (Photo by Huang Jingwen/Xinhua via Getty Images)

Xinhua News Agency via Getty Images

The UN Secretary-General set a high bar for this week’s climate summit in New York demanding new national climate plans for 2035 that went “much further, and much faster”. Against these asks and the tone set by the US President when he called climate change a “con job”, the event produced modest results. China put numbers on the table, Europe reasserted an intended range but not a final decision, Australia also reaffirmed its range, but disappointingly there were no other major announcements from G20 countries.

The centrepiece was undoubtedly China with its first commitment to an absolute reduction in emissions. Although President Xi’s pledge was conservative – reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 7-10% from peak levels by 2035 – he declared China would strive to do better, indicating Beijing’s intention to over-achieve this target. He also announced China would increase the share of clean energy sources in its energy system to more than 30%, and expand wind and solar capacity to 3,600GW by 2035.

The EU’s broader “statement of intent” – agreed recently by environment ministers – givesan indicative 2035 target to reduce emissions by between 66.25% and 72.5% from 1990 levels. Hamstrung by the delay in finalising its 2040 emissions reduction target, which has now been delegated to heads of state (where a group of Member States – including France and Germany – are slowing progress), Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s UN address struggled to maintain its climate leadership.

Elsewhere, Australia restated its target to reduce emissions by 62–70%. Like the EU’s wide range, it begs the question of where the country will settle and what level of delivery will follow. Ranges are political, offering direction without having to force agreement on a single figure. But in deferring the hard trade-offs, they increase uncertainty for business and investors.

Doing The Climate Math

By mid-evening, the arithmetic of the announcements framed the politics. According to the World Resources Institute, “By 2035, the world needs to cut 31.2 gigatons of emissions to stay on track for 1.5°C, or 20.2 Gt for 2°C. The NDCs and announcements so far would reduce that by just 2 gigatons – only 6% of what’s needed for 1.5°C and 10% for 2°C.” That is the immense gap the COP30 process must address.

Photo by Dominika Zarzycka/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

The road to Belém needs, therefore, to be two-track. First, governments should translate ranges into targets at the top end and publish the pathways to deliver them. World leaders must use the opportunity of coming together at COP30 to send a signal of this collective resolve to go further. A predictable and stable global system, built upon cooperation and healthy competition, gives business and investors confidence.

Second, the COP30 Action Agenda, that aims to mobilise businesses, investors, cities and civil society to scale solutions, can play an important role, functioning as a delivery lane when negotiated text is thin. That delivery lane matters because other signals are already pointing in one direction.

Recent research shows demand for oil, gas and coal is set to slow or peak in the next few years. It also reaffirms that existing clean technologies have the potential to displace 75% of today’s fossil fuel demand. The Action Agenda must highlight key areas where policy can drive further action, bridging between governments in the negotiating halls and those investing in and working on real world solutions.

Green Is The Trend

Six hours of set-piece announcements at the UN may have felt long and underwhelming, but they signalled something larger: the world is shifting. A day after President Trump urged leaders to abandon efforts to curb warming, and as the EU falters, China doubled down, stating plainly that “green and low-carbon transition is the trend of the time”, resolving to do better and reminding major economies of their responsibilities to ensure all nations benefit.

Photovoltaic panels in the Gobi Desert in Hami, Xinjiang, China, September, 2025. (Photo by Costfoto/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

NurPhoto via Getty Images

China’s energy transition is clearly visible in the real

economy: rapid wind and solar build-out, large EV and battery industries, and grid expansion that together are pushing costs down and

reshaping supply chains. NDCs set the direction, but markets are moving faster than

politics right now. For business, this signals that, while policy remains uneven, investment planning must track the rapid expansion

of clean energy.

What Business Needs

What business needs in tandem is predictable policy that turns that trend into lower costs and faster build. The immediate levers are clear: targeted redirection of fossil fuel subsidies can level the playing field for scaling clean energy systems, alongside adequate investments and clear plans to build out grid infrastructure and storage solutions so electrification can scale, and power is affordable. Realigning incentives and backing them with grid and storage plans will give companies the confidence to commit factories, supply chains and jobs while making public spending work harder.

Geo- and national politics will continue to sway sentiment on climate action – Washington’s volatility, Brussels’ process, Beijing’s caution – but the investment thesis does not live in soundbites. It

lives in whether big economies back their pledges with investible climate plans, and whether permitting,

interconnection and wider clean energy infrastructure can move at the speed of capital. Where that happens first is

where investment, skilled jobs and talent will go.