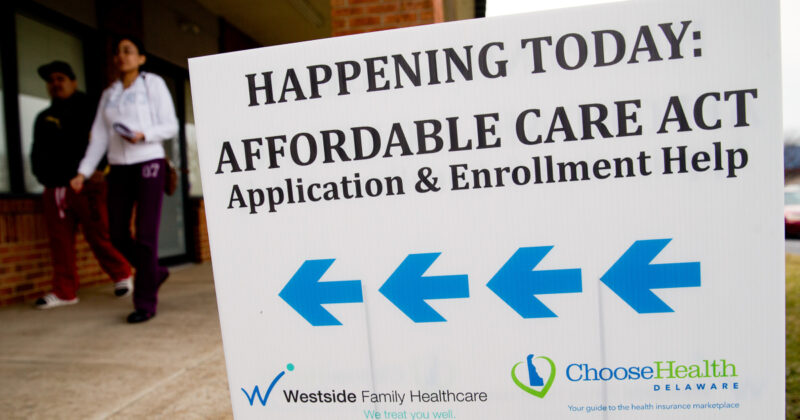

Affordable Care Act open enrollment kicks off Saturday, and this year’s enrollment period is expected to see the largest increase in costs since the law went into effect more than a decade ago.

More than 24 million Americans get their health insurance through the ACA, also known as Obamacare. In 2026, a perfect storm of rising premiums and the expiration of enhanced subsidies that kept costs lower for middle-class families mean many people will face higher bills or be forced to shop around for cheaper plans. Some plan to go uninsured as a result.

“It’s a high risk situation for people,” said Stacie Dusetzina, a health policy professor at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. “If it comes down to paying for food, power and heat versus health insurance that you don’t know if you’ll need or not, it’s hard to continue to pay for that given how much of your budget it takes today.”

Whether you’re renewing coverage or signing up for the first time, here’s what you need to know as open enrollment begins.

How long does ACA open enrollment last?

Open enrollment for ACA coverage runs from Nov. 1 through Jan. 15 in most states.

A few states have their own schedules. Idaho began its enrollment period on Oct. 15 and will close sign-ups on Dec. 15. Massachusetts will keep enrollment open through Jan. 23, Virginia through Jan. 30, and California, New York, Rhode Island and Washington, D.C., through Jan. 31.

If you want your coverage to begin on Jan. 1, you’ll need to enroll by Dec. 15 in most states. Plans selected after Dec. 15 will generally take effect Feb. 1.

Until this year, people with lower incomes — earning up to about 150% of the federal poverty level, or roughly $23,500 for an individual — could sign up for ACA coverage at any time, not just during open enrollment. That option has now ended.

The change took effect Aug. 25 after insurers raised concerns that some people were waiting until they got sick to sign up for coverage or later switching to a more generous plan that offered better coverage for their illness, said Cynthia Cox, director of the program on the ACA at KFF, a nonpartisan health policy research group.

The Trump administration has also revoked ACA coverage for DACA recipients, also known as Dreamers, for people who were brought to the United States illegally as children. Dreamers became eligible for coverage during the 2025 open enrollment, but it was revoked in August after the rule change.

Why are premiums going up next year?

Two main factors are driving next year’s premium hikes: the expected expiration of enhanced ACA subsidies and, to a lesser extent, higher rates from insurers.

The enhanced subsidies — put in place in 2021 — have helped millions of middle-class Americans pay less for their monthly premiums. The issue is at the heart of the government shutdown, with Democrats saying they won’t vote to reopen the government unless the tax credits are extended.

At the same time, insurers are raising rates for next year to keep up with the growing costs of hospital care and prescription drugs and an increased demand for medical services.

A KFF analysis found that insurers are raising premiums by an average of 30% in states that use HealthCare.gov, and by 17%, on average, in states that run their own marketplaces.

“The premium increases are the biggest we’ve seen since the ACA exchanges were set up,” said Gideon Lukens, a senior fellow and director of research and data analysis on the health policy team at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a nonpartisan research group. “At the same time, they’re a lot smaller than the out of pocket increases due to the expiring enhancements.”

Combined with the loss of enhanced subsidies, some people could pay 114%, on average, more in premiums, Cox said.

“It’s a double whammy,” she said. “People aren’t just losing the tax credits, but then they’re also paying this steep increase in what insurance companies are charging.”

Who qualifies for the enhanced subsidies?

Before 2021, only people earning up to 400% of the federal poverty level qualified for ACA subsidies.

The enhanced subsidies raised the income limit on who qualified, expanding eligibility to many middle-class people. People earning more than 400% of the federal poverty level — about $78,800 for an individual or $163,200 for a family of four — could get the tax credits if their premiums exceeded roughly 8.5% of their income. The enhanced tax credits boosted the amount of help people received.

“The reason why we call them enhancements is because they expanded eligibility, and they also increased the credit for everybody,” Lukens said. “It really led to an incredible amount of enrollment.”

This year, about 22.3 million people — 9 out of 10 ACA recipients — got the enhanced subsidies, according to government data.

Art Caplan, the head of the medical ethics division at NYU Grossman School of Medicine in New York City, said many of the people who get their insurance through the ACA work at or own small businesses.

“These are the mom and pop shops,” he said.

What happens if the enhanced subsidies expire?

The Congressional Budget Office projects that an average of 3.8 million people will drop their coverage and become uninsured annually over the next 8 years.

For those who keep their coverage, “it’s likely that they would pay more than twice what they’re paying now,” Lukens said.

“We’ll revert to a system where there’s a benefit cliff,” he added, “where a 60-year-old couple will no longer get any assistance in buying their premiums and will have to pay the full amount out of pocket.”

A 60-year-old couple making $85,000 a year could pay around $2,000 more in out-of-pocket premiums — from around $600 a month to around $2,600 a month, he said. A family of four earning around $130,000 could see their monthly premiums increase from around $920 to $1,900.

Can you still get help paying for insurance?

If the tax credits expire, people earning less than four times the federal poverty level — about $62,600 for an individual or $128,600 for a family of four — will still qualify for the standard ACA subsidies, Cox said.

But the amount of assistance they get will be significantly smaller, meaning they will also see higher premiums.

“They’ll still get a subsidy,” Cox said. “They’ll just get less financial help.”

Lukens said that some people with low incomes who qualified for plans with no monthly premium under the enhanced subsidies may lose that benefit, and there’s concern that many of them will drop coverage.

“There are estimates that roughly a million of this lowest income group of enrollees will likely become uninsured if the enhancements aren’t extended,” he said.

Others who no longer qualify for the tax credits may be able to find more affordable coverage by switching from a silver plan to a bronze plan, Cox said. Bronze plans typically have lower monthly premiums but higher deductibles, meaning you’ll pay more out of pocket before coverage kicks in.

Cox advised making sure the deductible is an amount you can realistically afford if you need care.

“What’s covered by the deductible?” she said. “Maybe there’s preventive services, maybe there’s doctors visits or other things that don’t apply to the deductible. So read the fine print.”

Is it cheaper to drop health insurance entirely?

Some people are weighing this option — putting the money they would have spent on premiums into savings.

Experts warn that’s a risky move. Paying cash can sometimes save money on smaller, predictable expenses — like an X-ray, or a routine lab test — but health insurance is meant to protect against unexpected, high-cost emergencies. A single hospital stay or surgery can cost tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars out of pocket.

“It’s what happens when people can’t afford coverage,” said Dr. Adam Gaffney, a critical care physician and assistant professor at Harvard Medical School. “It’s not a situation most people want to be in.”

Clinics known as federally qualified health centers can offer low-cost primary care to uninsured patients, and some doctors may negotiate — though they often require upfront payment, said Michele Johnson, executive director of the Tennessee Justice Center, a law firm and nonprofit advocacy group that helps people dispute medical bills.

Co-ops, also known as community based self-insurance, can offer lower premiums and more flexibility, Caplan said. However, they’re often not ACA-regulated and could leave members on the hook for large medical bills, he said.