In 1959, six years before I was born, Pakistan was ruled by a general who had seized power in a military coup and elevated himself to the rank of Field Marshall—the highest rank in the British army, whose structures and hierarchies were inherited by several post-colonial nations.

One of Field Marshall Ayub Khan’s main claims to power was that he was best friends with American president Lyndon B Johnson. Their mutual bonhomie is preserved in several portraits. Field Marshal Khan patting President Johnson on the cheek; President Johnson approaching a camel cart driver on a Karachi street and asking if he would like to be friends with him.

Field Marshal Khan must have had some doubts about the nature of their relationship because he ended up writing a book about it and called it Friends, Not Masters. Its Urdu translation has a more poetic and more self-serving title: Jis Rizq Se Aati Ho Parwaz Mein Kotahi. Borrowing from a poem about the spiritual and the moral struggles of the self by our national poet and philosopher Muhammad Iqbal, it boasts that what America feeds us will not stop us from soaring high.

America had no business feeding Pakistan as it was an agricultural country with famously fertile lands. More than American grains, Field Martial Ayub Khan needed American patronage to keep a handle on the political opponents at home and show his mother institution, the armed forces, that he was a close buddy with the most powerful man in the western world. What did Lyndon Johnson want in return, besides friendships with a military dictator and Karachi’s camel cart driver? A Cold War geo-strategic fling which allowed the U.S. the use of an airbase in Pakistan’s north to fly reconnaissance flights over the Soviet Union.

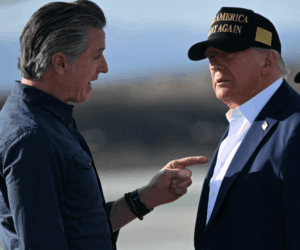

As I enter the 60th year of my life, Pakistan has its second Field Marshal. Soon after a brief and dangerous conflict with India in May, Asim Munir, the general leading the Pakistani army, was promoted to the rank of Field Marshall. He is also the first head of Pakistan army, who without staging a coup, has been invited to an official lunch meeting at White House. President Donald Trump said he was honored to meet him. Pakistan nominated Trump for the honor he covets desperately: the Noble Peace prize.

Pakistan has all the trappings of democracy, a parliament, a prime minister, judiciary, a noisy press but after putting the country’s most popular leader Imran Khan behind bars two years ago, the army calls the shots. It’s no surprise that Trump instead of wasting time with civilian figureheads extended his hand of friendship to the man who matters.

America has always had a soft spot for Pakistan’s military dictators because they see them as a one window operation for their secret, and not-so-secret, strategic plans. Throughout the 1980s, America bankrolled the brutal military dictatorship of General Zia ul Haq because he was helping Washington defeat the Soviets in Afghanistan. When General Pervez Musharraf overthrew an elected government in the late 1990s, he became an international pariah.

After America was attacked on Sept. 11, 2001, the Bush Administration embraced General Musharraf when they needed his cooperation to invade Afghanistan. The beginning of this new courtship was typical of U.S.-Pakistan love lore. General Musharraf claimed that a senior American official threatened to bomb Pakistan into stone age if it didn’t comply. What’s a general to do? He offered full cooperation and gave Americans excess to Pakistan’s air bases to bomb its supposed Taliban brothers in Afghanistan.

The relationship really bloomed. General Musharraf became a bounty hunter for Washington: handing over Taliban leaders, even their ambassador to Pakistan, to Americans who hooded, gagged, handcuffed and dispatched them to black sites or put them on flights to Guantanamo Bay. On many occasions innocent Pakistani citizens were handed over just to make up the numbers.

It’s mostly during the civilian governments that relationship between the U.S. and Pakistan has soured and foreign affairs experts have to roll out relationship metaphors to describe this sordid affair. Cheated on, used and dumped, jilted lovers—everything has gone into this toxic mix. When Hillary Clinton visited Islamabad and in a town hall lectured Pakistanis about keep snakes in the backyard, the U.S. was called a “mother in law” who is never satisfied.

In his first term, President Trump wasn’t happy with Pakistan and described its establishment as deceitful. Islamabad had failed to deliver what Washington had wanted in Afghanistan. In the second Trump term, that old love between America and Pakistan seems to have been rekindled by what brought them together in the past: their “cooperation” in the “war on terror.” Last year, Pakistan army arrested and handed over an Afghan citizen, the alleged mastermind of an attack on Kabul Airport that killed more than 200 Afghans and about a dozen Americans. President Trump thanked Pakistan in his first state of the nation address.

Donald Trump is not the first American President to look at this strong army and think I can put them to some good use. Field Marshal Asim Munir is not the first Pakistani general to believe that even an abusive relationship with the U.S.—a bit of a master, a bit of a friend—helps him maintain the military’s grip over power in Pakistan.

Munir’s army has the country at a choking point. They can handpick the ruling party, choose the opposition, fix the courts, steal the elections. Their business empire is more sprawling than ever: from real estate to fertilizer, from breakfast cereal to amusement parks.

But Pakistan’s armed forces do have a really solid side hustle in professional soldiering. In recent skirmishes with India, it surprised international defense analysts with its agility and preparedness. American generals probably noticed that that their old ally can still hunt.

Yet while the Pakistan army is claiming, celebrating victory over India and flaunting Field Marshall Munir’s halal lunch with President Trump, its popularity at home is at an all-time low. Inter Services Public Relations, the public relations wing of the Pakistan army, can’t even say, “Asslam ul alaikum” on its social media handles without attracting a torrent of abuse and insults from the political opponents.

A close relationship with the U.S. is no guarantee of popularity at home. People can see through the façade of strategic alliance and promises of exploring Pakistan’s “massive oil reserves.” After Trump’s discovery of oil in our country, Pakistani internet exploded with memes about of canisters of cooking oil we use in some of our favorite foods. Not even the most delusional Pakistanis believe that the country has any oil reserves.

We have watched this love story before. It never ends well. In Afghanistan it ended with scores of Afghans dangling from the retreating American planes and falling to their death. More than 70,000 Pakistanis were killed in the two decades of our military’s cooperation in the American war on terror. And every few months, Pakistan has returned to the International Monetary Fund boardrooms to keep its economy afloat.

Among the ordinary citizens of Pakistan, there’s an undercurrent of resentment against American hegemonic power that erupts into bursts of hatred when they are unhappy with their own rulers, who they see as extensions of American power.

All it takes is the lighting of a match to test our ruler’s bond with their patrons in Washington. A political worker once told me that whenever their party is in power and they need something done all they need is an American flag, a match box, and a camera. If you don’t accept our demands, we’ll take this matchstick to the American flag and take a picture, and then we’ll see what America really thinks of you. Friend? Master? Or that double-dealing old ally who can still hunt?