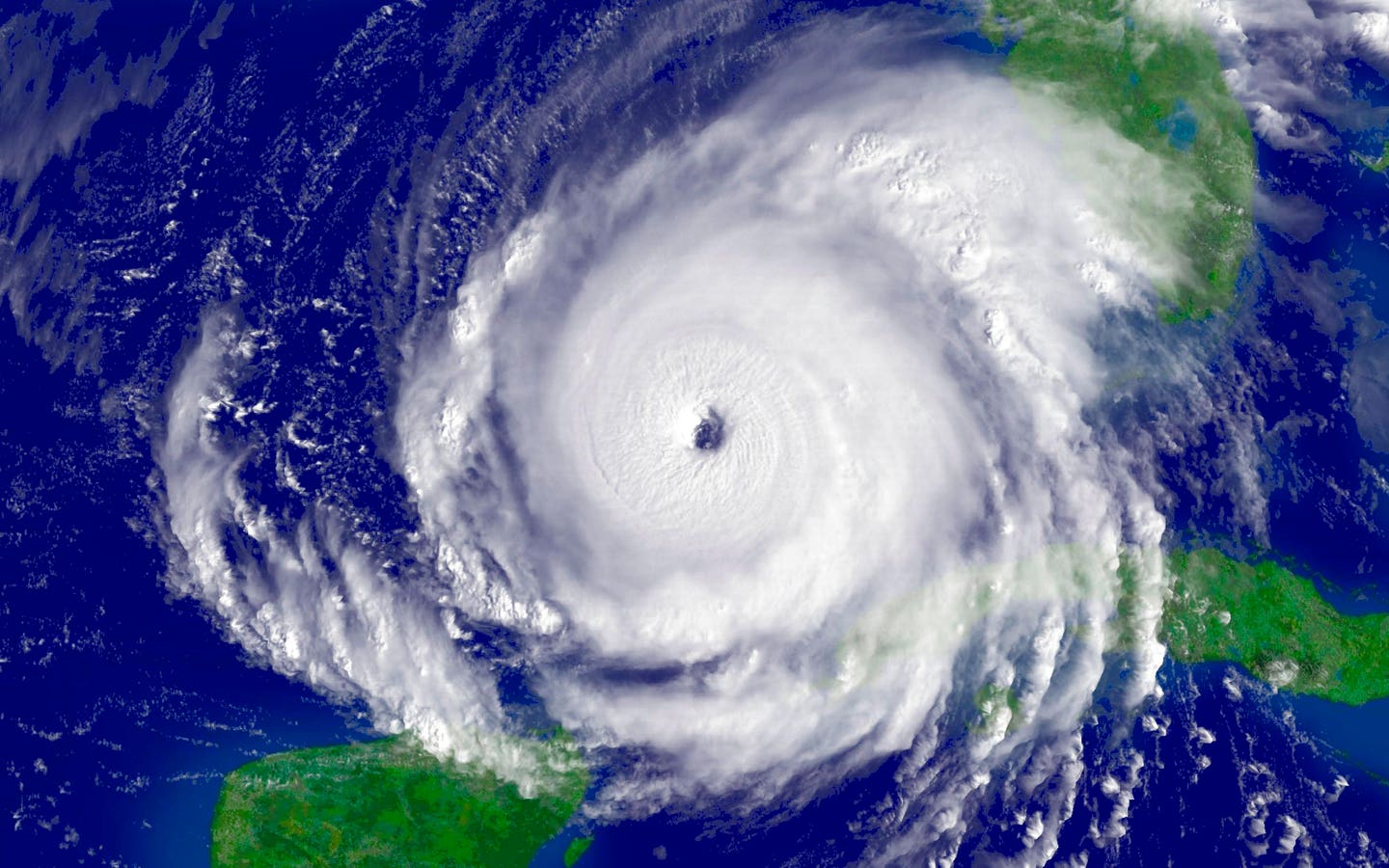

The 2025 Atlantic Hurricane Season has seen three named storms to date, but meteorologists warn not … More

The 2025 Atlantic hurricane season officially began on June 1, yet we’ve seen remarkably little activity compared to the hyperactive seasons of recent years. By this point in 2024, we had already tracked five named storms, including two hurricanes. This year, three named storms, Andrea, Barry and Chantal, have reached tropical storm strength. Only Chantal had impact on the U.S. mainland, causing minor coastal flooding and brief power outages along parts of the Southeast coast. So, despite record global sea surface temperatures, why have storms failed to form?

Tropical storm development requires multiple variables aligned.

That’s because not all the ingredients required for tropical development are lining up.

The main development region, or MDR, where many long-track hurricanes are born, isn’t as warm as last year. Meanwhile, the western Atlantic and Caribbean are hot, but upper-level wind patterns there have been actively working against storm formation.

Warm Water Isn’t The Whole Story

Hurricanes need more than just warm ocean water. They also require a disturbance in one of the typical development regions, as well as relatively calm upper-level winds. Without these, tropical systems struggle to organize and grow.

The primary culprit behind this year’s unexpectedly quiet period is persistent wind shear across the tropical Atlantic. Wind shear, the change in wind speed and direction with height, acts like a lawn mower to developing tropical systems, essentially cutting off the tops of thunderstorms before they can organize into coherent tropical cyclones.

Tropical waves rolling off Africa are either encountering this unfavorable environment to the west or struggling to survive in the cooler MDR. The basic ingredients are scattered and haven’t come together in the same place at the same time.

Stronger-than-normal upper-level winds across the Caribbean and western Atlantic are suppressing … More

Sinking Air Is Suppressing Storms

Another factor working against storm formation is the broader pattern of vertical motion in the atmosphere. From late June through early July, NOAA analysis shows an area of widespread sinking air over much of the Atlantic. This pattern makes it harder for thunderstorms to build and organize, even when sea surface temperatures are warm. Tropical systems need rising air and upper-level support to develop and grow. Until that large-scale atmospheric pattern shifts, the Atlantic will remain a less favorable environment for storm formation.

The Climate Change Connection

Climate change is also playing a role, though not in the way some might expect. Warmer oceans are now spreading farther from the equator and expanding into the tropical zone. At the same time, the warm, storm-fueling air near the surface is reaching higher into the atmosphere.

That might sound like a recipe for more hurricanes. However, as Nate Hamblin, Senior Tropical Risk Communicator at DTN, explains:

“Storm development also depends on instability — the contrast between warm surface air and cooler air aloft. As the upper atmosphere warms, that contrast weakens. This means it now takes even hotter sea surface temperatures to create the same storm-friendly environment we saw in the past.”

Basically, climate change is shifting the threshold. It’s not automatically fueling more storms but rather changing the rules for when and where they can form.

The Forecast Is Steady But The Risk Remains

Despite the current lull, forecasters still expect an above-normal season. The NOAA outlook calls for 13 to 19 named storms, 6 to 10 hurricanes and 3 to 5 major hurricanes. DTN, the company I work for, forecasts 19 named storms, 9 hurricanes and 4 majors. Colorado State University recently trimmed its numbers slightly to 16 named storms, 8 hurricanes and 3 majors citing persistent wind shear and less favorable conditions in June and early July. These adjustments are modest, and not unusual. More importantly, they reflect a shift in timing and not a drop in overall risk. The concern isn’t about how many storms will form, but how quickly conditions may flip and how little lead time we may have once storms develop.

If shear weakens and the water temperatures in MDR warms, we could move quickly from dormant to dangerous. These will be areas forecasters will be watching closely in the coming weeks.

Signs Of Change To Watch

Subtle shifts in the atmosphere in July could change the trajectory of the season. Forecast models point to weakening wind shear and a possible eastward shift in the Madden-Julian Oscillation – signals that rising motion may soon return to the Atlantic. If that happens, and with plenty of ocean heat already in place, storm development could ramp up quickly. That can change fast.

Don’t mistake the current lull for lasting safety, especially for coastal communities, emergency managers and businesses. The ingredients for hurricanes in 2025 are still out there and just waiting to align.