Sharks stood out as a particularly targeted group. Of the 546 vetted listings, 61 percent were advertisements for shark trophies, most often jaws.(Photo by Creative Touch Imaging Ltd./NurPhoto via Getty Images)

NurPhoto via Getty Images

When most of us think about online shopping, we picture secondhand clothes, the latest fad (ahem, Labubus), household gadgets, or maybe a rare collectible. But the same digital tools that connect us to everyday goods are also quietly fueling a darker industry: the trade of endangered species. From the comfort of a laptop, tablet, or phone, anyone can buy body parts of threatened animals… sometimes with just a few clicks.

Direct exploitation of wildlife has long been a key driver of extinction. Species across the globe are hunted, captured, or harvested for food, medicine (be it rooted in science or not) or to be a fashion think-piece or tacky souvenir. Some of this trade is legal and regulated, but much of it isn’t, and the World Wide Web has made it easier than ever for buyers and sellers to connect. What once required shady in-person networks and meeting up in darkened alleyways (at least, that’s how I picture these sorts of deals doing down) can now happen openly online, often hidden in plain sight. Yes, the person next to you on the subway or sitting next to you in a coffee shop might be shopping for a pangolin or a real tiger rug while you’re hitting “confirm” for your weekly grocery shop.

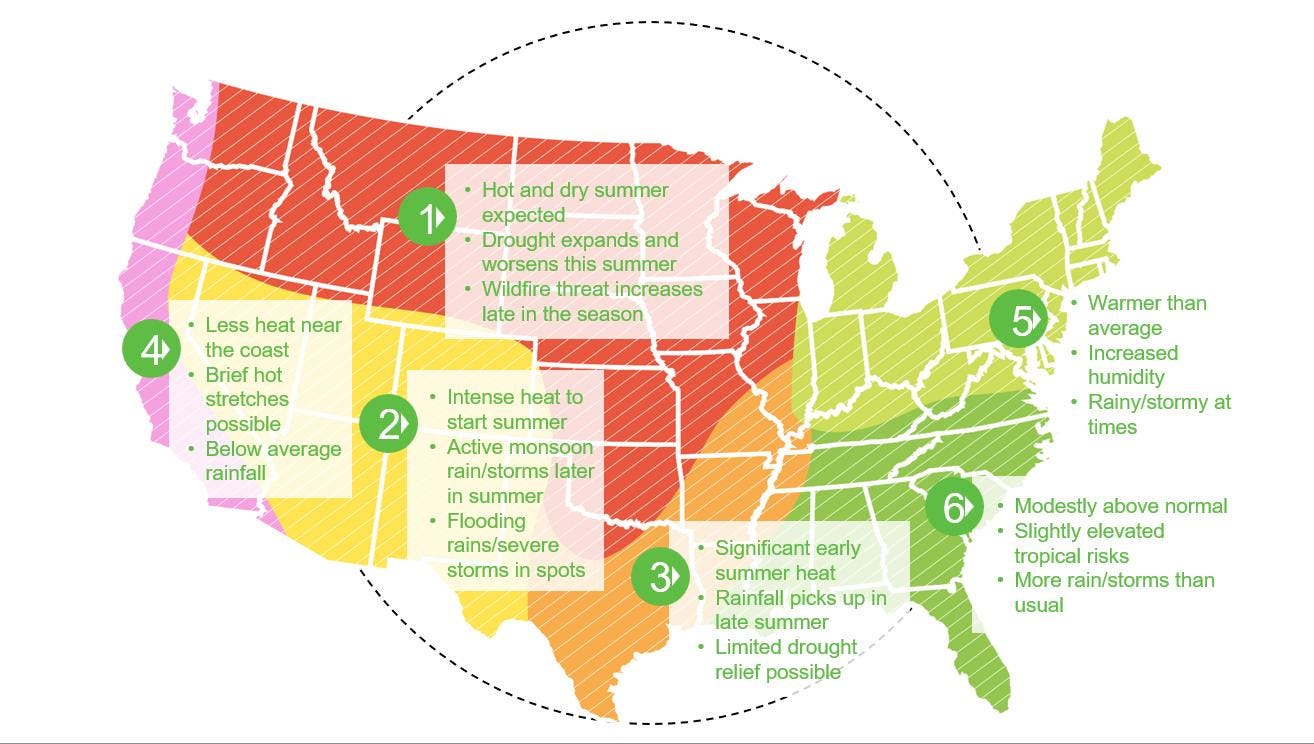

To better understand this problem, researchers developed a tool that automatically scanned 148 English-language online marketplaces over a 15-week period in 2018. Led by Associate Professor Dr. Sunandan Chakraborty of the Luddy School of Informatics, Computing, and Engineering at the Indiana University, the team focused on more than 13,000 species identified as at risk of extinction by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, as well as 706 species listed under Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (of special note: international commercial trade of CITES Appendix I species is prohibited). The initial sweep was massive, pulling in 10,699 unique listings, offering everything from individual animal body parts to eggs. But filtering and careful manual review narrowed that down to 546 genuine sale listings, representing 83 different species. Among the 83 species for sale, 18 were protected under CITES Appendix I. That means these transactions were not just questionable but likely illegal under international law. Even more surprising was the discovery of 13 species whose intentional exploitation had not previously been recognized as a threat by the IUCN. In other words, researchers uncovered a demand that conservation assessments had missed — proof that the online marketplace can expose emerging risks before they show up in official data.

Sharks stood out as a particularly targeted group; of the 546 vetted listings, 61 percent were advertisements for shark parts or “trophies,” most often jaws. Even more concerning, nearly three-quarters of those trophies came from species already listed as endangered or critically endangered. These are predators that face huge population declines due to overfishing, bycatch, and habitat loss, yet they are still being carved up and sold as wall décor.

A pangolin skin is displayed amongst other exotic and illegal animal parts at a stall on February 17, 2016 in Mong La, Myanmar. (Photo by Taylor Weidman/Getty Images)

Getty Images

But let’s back up for a second: how exactly did the researchers go from over 10,000 listings to just under 550? It all has to do with what words have been used to describe what is on sale. Keywords like “ivory” or “horn” can refer to everything from jewelry to musical instruments. The filtering process shows how tricky it is to separate real wildlife trade from unrelated items. They also discovered how concentrated the trade is. Just four websites hosted more than 95 percent of the “genuine” listings. This kind of clustering means that if conservationists and regulators can better monitor and enforce rules on a handful of platforms, they might significantly reduce online trafficking. But, at the same time, it also underscores a challenge. While they may successfully shut down sales on one site, that often pushes the seller to sell their goods on another, and the global nature of the internet makes consistent enforcement difficult.

The use of automated tools shows promise for spotting patterns across sprawling marketplaces. But, as the team points out in their publication, the study period was just 15 weeks and was limited to English-language sites, which means the true scale of the trade is almost certainly much larger. Wildlife traffickers are adaptable, and when regulations or monitoring improve in one space, they often shift to another. For example, a banned auction on a public site might reappear in a private Facebook group, where sellers admit new members only after vetting them. Messaging apps like WhatsApp, Telegram, or WeChat, with their encrypted conversations and group features, have become particularly attractive to for blackmarket dealings (such as drug dealing) because they allow transactions to occur beyond the reach of most automated monitoring tools; could they be used for wildlife trafficking? Possibly! And for those still using mainstream messaging methods, code words or emojis can replace species names to avoid detection, making it even harder for authorities to track illegal activity. Afterall, you can’t arrest everyone who uses a tiger or elephant emoji.

Listings in other languages add another layer of complexity, since the wildlife trade is global and not confined to English-speaking markets. Species names and sales terms vary across regions, with sellers often using local dialects, slang, or even misspellings to avoid detection. For instance, ivory might be listed under Mandarin characters, while shark fins could be advertised using Spanish or Portuguese fishing terms. What the researchers found in English marketplaces is almost certainly a fraction of the whole picture, with many more listings hidden in non-English platforms. What looks like a relatively small market on the surface could in reality be a sprawling underground economy that adapts as quickly as researchers and regulators try to keep up. Unfortunately, the animals caught in the crossfire don’t have time on their side. Many of the species found for sale already struggle with shrinking habitats, climate change, and pollution. Adding targeted exploitation into the mix increases their risk of extinction. For sharks in particular, the irony is painful: even as global campaigns call for their protection, their body parts are still being openly bought and sold online.

Addressing this problem requires cooperation across multiple fronts. Marketplaces must take more responsibility for monitoring and removing illegal wildlife sales. Governments need to enforce existing laws and close loopholes. Conservationists can use tools like the one in this study to track and flag emerging threats faster. Building tools that can scan across multiple languages — and adapt to evolving terminology! — will be one of the biggest challenges for monitoring the online wildlife trade. And what can the general public do? Be aware! The wildlife trade doesn’t just happen in remote markets but also on mainstream websites, and knowing that can shift how we think about our role as consumers.

The online trade in endangered species is a reminder that extinction isn’t always driven by forces beyond our control… sometimes it’s as simple, and as devastating, as an online listing with a “Buy Now” button. The internet has the power to connect people across the globe, but in this case, it is also connecting extinction to our doorsteps.