A federal judge last week approved a $2.3 million settlement in a class action lawsuit against a small program for troubled teens in Wyoming, ending four years of litigation over allegations of forced labor.

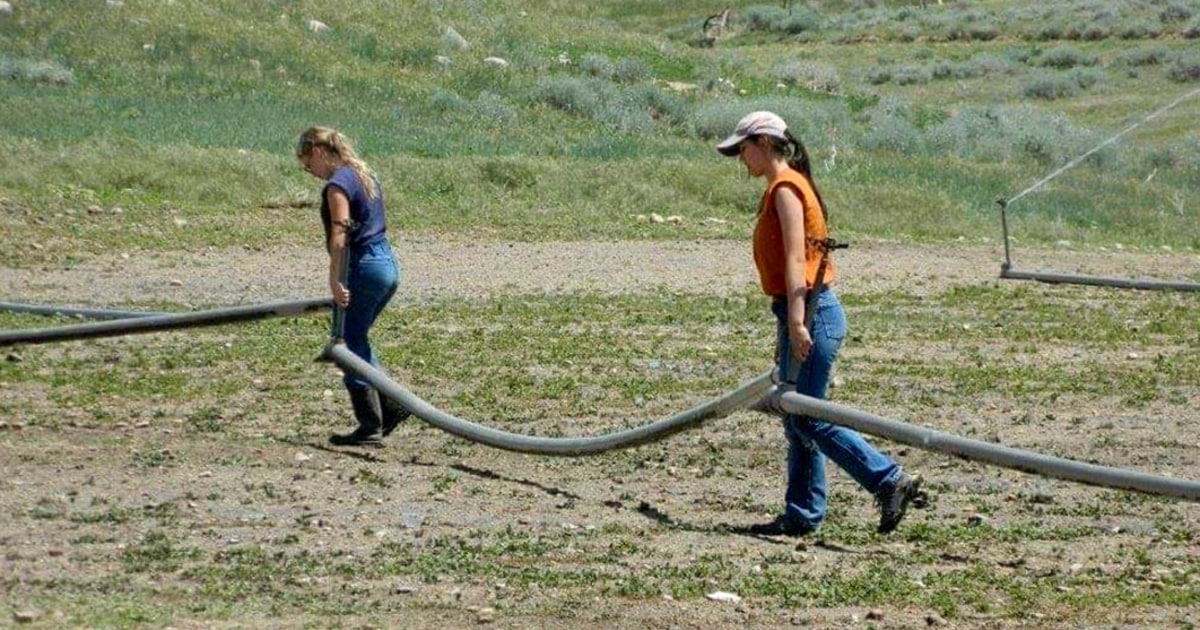

Trinity Teen Solutions promised to help girls with mental health and behavioral problems, but a group of women who’d been placed there as teens by their parents accused the now-defunct ranch of forcing them to perform manual labor. Tasks included repairing barbed wire fences, castrating animals and laying irrigation pipes, the suit alleges. Injuries were disregarded, it states, and the girls were subjected to humiliating punishments if they did not do the work as ordered.

Attorneys for Trinity Teen Solutions declined to comment. The settlement stipulates that Trinity Teen Solutions and its owners are not admitting wrongdoing. In previous court filings, the ranch said it did not violate the law and that “chores and physical exercise were part of its program.”

An NBC News investigation in 2022 revealed that the former clients had tried to report their concerns about Trinity Teen Solutions to state officials and law enforcement, and described them on social media and business review websites like Yelp. State officials allowed Trinity Teen Solutions to keep its license, and its owners were never charged with a crime. A Wyoming Department of Family Services senior administrator told NBC News at the time that the state was hesitant to shut down youth facilities unless children were in danger.

Trinity Teen Solutions also sued three women who’d criticized the ranch online in 2016 for defamation, in a case that settled without details being made public.

The new settlement, which was submitted in court last month, will be open to anyone who’d been placed at the ranch from November 2010 until it closed in 2022, and performed “agricultural labor” — more than 250 people in all. Each person’s cut of the settlement will be based on how long they were at the ranch, which was typically one or two years.

Those who join the class and receive a settlement check will have to adhere to a nondisparagement agreement, meaning they cannot bash Trinity Teen Solutions or its owners online, but the court filings state they are not prevented “from making true statements about their experiences.”

Amanda Nash, one of the lead plaintiffs, who was sent to Trinity Teen Solutions 10 years ago, said she felt relieved by the settlement. “I was just very happy to be able to give the 15-year-old me a voice, and be able to try my best and represent dozens of other girls — whether they wanted to be involved or not — to try and speak up for them as well,” she said.

But Anna Gozun, who was sent to the ranch in 2012, said she won’t take part in the settlement because of the nondisparagement agreement and the fact that Trinity Teen Solutions’ owners didn’t have to admit wrongdoing. The settlement “does not reflect true accountability or justice,” she said.

“It’s disheartening beyond words,” Gozun continued. “Many of us came forward at great personal cost, reliving trauma in hopes of stopping a cycle of abuse. This settlement feels more like a forced ending than a fair resolution.”